Recently, I gave a lecture at the first ever World of Darkness convention in Berlin, run by the fantastic people at Participatory Design and the team behind World of Darkness. And I was fortunate enough to be featured in a post on White Wolf’s Facebook feed with a couple of my slides. Since then a lot of folks have contacted me wanting to know if my talk was recorded. Sadly, the answer is no. However, I decided to not only make my slides available online, but to do a post here outlining the talk a little more. So, without further ado, a little post on what I call Integrating History In Your Game With Respect. ( You can download and follow along with the slides here.) Enjoy!

Back in 2004, I joined the New York Larp community. Until then, I’d only done roleplaying online, where I’d participated in online chat RPG games since as early as 1994. And like most RPGs, there was an element of incorporating historical events into the history of those games and characters. I’d played vampires who lived through the American revolution, or else explored steampunk settings with plenty of historical baggage (a favorite was the Hindenburg explosion). But it wasn’t until after 9-11 that I encountered a personally difficult historical event that intersected directly with my own background.

In The Shadow of 9-11

Before 9-11, a lot of the larps in New York City used a location called the Winter Garden, which sits just across the street from what used to be the Twin Towers. It was a beautiful building with a glass atrium that gave fantastic views of both the waterfront on one side and the World Trade on the other. But, like many buildings, it sustained heavy damage when the towers fell. In the wake of the terror attacks, the larp community of New York not only had to face the psychic and emotional trauma of a heinous terrorist attack on their city, but on a smaller level had to face losing a larp space they considered welcoming, available, and safe.

This almost symbolic violation of the Winter Garden represented an equally difficult question facing the gamers of New York, who often used the city as a backdrop for their games: how do they incorporate a major current event like 9-11 into the settings of their games? And more importantly, should they?

As I said above, I didn’t join the larp community in NYC until three years later. Yet even then the ripples of 9-11 were felt. Every game I joined had made the same decision: 9-11 was not to be made the focus of the game, and the event itself was not to be considered a supernatural event in its origins. Though there were repercussions to, for example, Changelings in the New York area due to psychic trauma, the event itself was respectfully left to be an example of very human monstrosity and inhumanity.

More than years later, I recently checked in with a friend of mine regarding games being run in the area, only to be told that 9-11 was a major part of the plot line of a local game starting up. And they were including 9-11 as a plot point, supernaturally motivated and part of a greater conspiracy of monstrous darkness. I made it a point to say I’d never go to that game, no matter what.

Today, the Winter Garden has been rebuilt and I’ve visited to run scenes there when I ran larps in New York City. But only once. The place stands in the shadow now of the Freedom Tower, but its proximity to the 9-11 memorial and the ground where so much pain happened in September 2001 leaves a scar I, as a New Yorker, can’t face on a regular basis. And that same scar haunts any game I know that includes 9-11 as a plot point. For me, there is not enough distance, not enough time. I don’t know if there ever will be.

Today, the Winter Garden has been rebuilt and I’ve visited to run scenes there when I ran larps in New York City. But only once. The place stands in the shadow now of the Freedom Tower, but its proximity to the 9-11 memorial and the ground where so much pain happened in September 2001 leaves a scar I, as a New Yorker, can’t face on a regular basis. And that same scar haunts any game I know that includes 9-11 as a plot point. For me, there is not enough distance, not enough time. I don’t know if there ever will be.

It’s this situation that made me consider the historical events of the past and the ways in which we include them in our games. There is an inherent question to fictionalizing events that challenges us as creators and writers: how do we respect the immensity of tragedies gone by, of wars and genocides and monumental losses across history, enough to include them in our work while still giving weight to their historical importance? We can’t tiptoe through art, but how do we avoid using history as a convenient plot point, without acknowledging the very real scars these events have carved through history?

History As Set Piece, Plot Point, And Setting

There’s no question art and specifically fiction has been made about historical time periods forever. Shakespeare wrote pieces set in the time of previous monarchs. Folklore is chock full of retellings of wars long past, starting as early as the stories of Troy. Art has been as much about capturing sentiment and idea as it has about recording the events going on in our cultures. When writing, history is the backdrop of the stories we want to create, whether serving as the framework for a period piece or acting as inciting incidents to other stories. We fictionalize historical events to explore them further, to put them in new contexts, and to give them new life in our memories.

When including historical events in games, however, we are taking that fictionalization one step further. We’re asking our players to inhabit those time periods, or to directly reflect on the historical events in question as they relate to the characters they’ll be inhabiting for a time. Using the example of World of Darkness games, immortal monsters like the vampires in Vampire: the Masquerade and the New WoD Vampire: the Requiem have existed for hundreds of years and bore witness to countless horrific, cruel events. Some of them, the game books posit, were even influenced and made worse due to the machinations of these inhuman beings. Even the slightly brighter settings of Mage: the Ascension and Changeling: the Dreaming have deep historical ties, reframing historic events like the first nuclear tests or the moon landing as part of a tapestry of events influencing the game setting as a whole and player characters on a microcosm.

While including those historical events is a very typical artistic and game design choice, a difficult problem occurs when facing the enormity of context in connecting to a historical time period and its events.

For example, three games in the White Wolf catalogue are setting books directly framed by historical time periods with deeply troubling events going on within. Games like Vampire: Dark Ages, Werewolf: The Wild West, and Victorian Age Vampire provide settings with rich, engaging, and honestly just fun time periods to explore. I mean, who wouldn’t want to play a werewolf in the Wild West, or a vampire sweeping through the salons of England during the Victorian era? But each of those time periods carries with it burdens of difficult historical context, some of which lies outside of what many deign to include in their retellings of the past.

A setting like Vampire: Dark Ages carries with it not only the historical complexity of Dark Ages Europe, but the weight of hundreds of years of mass religious persecution and violence. Werewolf: the Wild West exists in the shadow of American expansion and the genocide of the native populations of North America. And let’s not even get started on the horrors of colonialism, sexual and gender repression, and economic disparity often ignored when exploring the ‘glorious’ time of Queen Victoria.

It’s easy to gloss over hard truths about what went on in a time period in favor of just engaging with the fun parts for our games. But in doing so we are washing away the trauma for watered-down, stereotypical, lionized history. There is no separating the hard truths about the past without making a tacit choice to ignore them in favor of your fun. And while that may be a choice you as a designer and a player, it is just that: a choice. And every choice has implications, and says something about the ethos you’re backing with your design.

How To Integrate With Context

So looking at this enormous question, how does one integrate historical events with respect?

The first step, in my eyes, has already been mentioned: provide context. When creating your game setting or your game, acknowledge the difficult historical events and societal troubles, explore the complexity of them from more angles than just the dominant narrative, and reflect on how those tragedies affect people not only in the setting but perhaps even around your game table.

I’m a particular fan of using examples for things, so let’s explore one of my favorite time periods to pick on…

…ancient Rome!

Now, as a setting, ancient Rome is a pretty cool place to set any piece of fiction and especially games. I mean, you get to explore some fun material. There’s Politics! Intrigue! Polytheism! Conquest! Sexual politics! Cool robes! Murder on the senate floor! Caligula! (I mean who doesn’t love Caligula?) There’s so many things to draw players into rich, complicated stories in an exotic and appealing time period and locale.

But historically, Rome was also kind of a shitty, horrible place.

Rome as an empire was built on the back of the conquest and near extermination of so many other cultures. The Romans rolled into other countries, slaughtered thousands, murdered religious leaders, raped and pillaged, and then subjugated the conquered people to be ruled and controlled by them. They systematically interrupted the course of cultural evolution of entire civilizations to expand their empire. Because really, that’s kind of how empires work and have worked since maybe the dawn of time. This stands true for the Mongolians, the British, and the ancient Egyptians. Check out non-fictional stories about those time periods any time and you see, beyond the glitz of the beautiful centers of power, you get the story of the categorical destruction of millions of people’s lives.

Now one might say ancient Rome is far enough back in history, you’re certainly not going to run across someone who was directly involved in the horrors of ancient Rome enough to be offended or hurt by the white-washing of the follies of the Roman Empire. (Unless you have a real immortal at your table, in which case my next advice is even more important). But what you might have at your table is someone whose family and culture was directly influenced by the slaughter the Roman’s perpetrated during their marauding conquests. While many can look at the Romans and laud them for their efficiency in bringing new evolutions to society as a whole, others are descendants of those whose people were massacred in the name of that progress, who still have stories passed down about the losses their people suffered. And the history of those events is still deeply felt.

A good example, honestly, comes from Jewish history. While lots of people think the Romans are pretty cool, Jews have an entirely different context for Romans. For anyone who hasn’t read Jewish history or watched Ben Hur, The Passion of the Christ, or Jesus Christ Superstar, the Romans were utter dicks to the Jews. They occupied and ruled Judea from the sacking of Jerusalem in 63 BCE all the way thru the reported life and death of Jesus until about 313 CE. The Romans sacked Jerusalem, destroyed the Jewish Temple, the center of Jewish spiritual and political life, and massacred not only huge parts of the population, but systematically tortured the greatest thinkers and leaders as an example to the population to make sure they wouldn’t revolt. For nearly four hundred years, the Romans committed atrocities to suppress the population and put down revolts, many of whose stories are now largely ignored. And Judea was only one of the many provinces conquered. Countless cultures, religions, and countries had their histories forever negatively impacted by the Romans. But when have you explored all this in your tabletop or larp campaign?

Remember: one person’s ‘cool setting’ is another person’s ancestral horror story. And sensitivity to that fact provides a cornerstone of looking at respectful representation in your game’s narrative design.

How Hollywood Is Just Messing With Us

Another great example is the fun parts of Roman society people love to lionize. Specifically…

…gladiators!

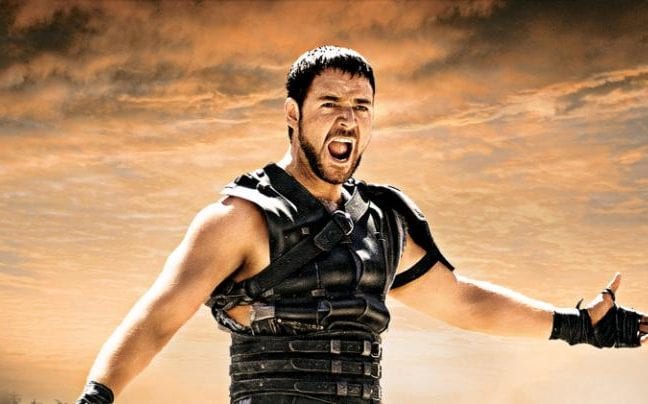

What isn’t fun about gladiators? You’ve got tough guys in armor fighting each other for the evil leaders of Rome, all decked out in armor, facing the chance of death for the glory of the crowd and the slim chance of surviving long enough to be freed. It’s glitzy, sexy. It’s full of half-naked people running around, chopping off heads. It’s basically a sexier version of a dungeon crawl in D&D, only with the kind of raucous audiences that’d make today’s WWE fans look like polite little lambs. It’s dueling with a ten drink minimum and a TV-MA rating. Basically, to look at it in modern media, it’s hella sexy and fun. And whatever parts of it are considered wrong are framed in the typical two-dimensional good-and-evil questions. The rich Romans are WRONG, the gladiators are GOOD, and that’s about it. There is no complexity involved.

In other words, even the more complicated stories about gladiators (such as the Spartacus revolt) often get washed down to their most basic, uncomplicated components. Which often look a whole lot like this…

Yet below the surface, gladiatorial combat in Rome was part of the systematic oppression of marginalized and conquered people from across the Empire. Slavery was in fact a major part of Roman life, and along with servitude, forced military service, and systematic sexual coercion, violence as a means of entertainment was a way for the Romans to require slaves to integrate violent behavior into their lives while turning their anger and aggression at their enslavement towards one another instead of at their captors. It was a brutal, horrifying practice, used to at once pacify both the slave population and the larger ‘free’ people of the Empire, keeping them distracted from the inequity and corruption of the higher classes on the backs of the lower. (Man, sounds familiar, huh…?)

It’s too easy to include gladiators in a game as a fun, sexy setting event by focusing only on their most well-known portrayals from the media. When including historical context in your games, you run the risk of relying on the Hollywood History Treatment, where the events of history are retold through the streamlined, white-washed narrative developed for ease of filmmaking and in the name of good television.

(A fun note: the above photo is from the Spartacus TV series from Starz. And while it is effectively a visual orgy of blood, violence and, well, orgies, the show also has a surprisingly nuanced take on the complexities of slave life. It takes great pains to show the horrors of sexual violence, lack of consent, slavery, and coerced violence that existed as part of Roman life. While it includes a stunning amount of sex and some of the most glamorized gore I’ve seen in a show, it has a surprising amount of heart. Just take its historical accuracy with a grain of salt. This is Hollywood History at its most over-the-top).

A great example of this is the Wild West, which as a time period has perhaps suffered the most in terms of being reshaped in public perception thanks to Hollywood’s influence.

Thanks to Hollywood, the Wild West has gone from looking like this…

…to this.

A recent episode of Adam Ruins Everything was dedicated to debunking many of the ‘facts’ people know about the Wild West. Apparently, most of what we actually think of as fact about this time period is just what we’ve been programmed to think by Hollywood’s representation. And man, a lot of that representation just glosses over a lot of things, like the financial strength many women had in western towns, the complexity of native life before, during, and after the invasion of white settlers, and the damage done by white encroachment to immigrants such as the Chinese, or locals like the native Mexican populations. The West has been rewritten as the domain of the rugged white man, the lone cowboy or law man who rides into town and rescues the poor settlers, besieged by lawlessness and terror. Sounds like a great game setting! Too bad much of it is wrong, paving over the real difficulties and complexities of a fraught time period.

So when integrating historical events into your game settings, it’s key to recognize and communicate whether you’ve provided your players (or consumers) with the Hollywood History or a well-researched version of history. What research have you done? Does your experience with the time period only involve films, not documentaries? (It’s important to recognize also that many documentaries have very specific slants they put on historical events too, so be careful for bias even in non-fictional accounts).

Bear in mind, the Hollywood History of a time period can be a fun way to set a game. It’s just important to remember that much of that Hollywood-izing (a new term!) is very two-dimensional and can be disrespectful in terms of portraying difficult issues of the time. If you intend to use it as the basis of your game, it might be helpful to be up front about the kind of history you’re going to use. Listing the sources for your game up front can help let players know just how accurate you’re going to be to the time period versus utilizing Hollywood History instead. A great example of this is Vikings. If you were to use the TV show Vikings as the influence for a game, you’ll get a very different experience than if you do actual research. And, as many of my larper friends from Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland will tell you, nothing makes many of them grind their teeth more than the conflation of Hollywood Vikings with the real history of Vikings from their cultures.

But hey, some things can be sacrificed on the altar of fun… right?

Historical Figures In Games (or, No More Hitler Please)

Another place where games can run into difficult territory is the integration of historical figures as part of the game’s history or narrative. While many folks won’t have too much of a problem should you use a two-dimensional portrayal of the guy playing the violin while the Titanic sank (though that story is largely considered apocryphal by the way, sorry to burst THAT bubble), other historical people carry far more weight by their actions and legacies. Many games include mention or inclusion of some of histories greatest monsters as antagonists, contacts, or just cool little side bits. And while they can be great adversaries and evocative figures in your game, consider the real historical toll these folks had on real human lives when integrating them into your game.

Figures like Charles Manson, Jim Jones, tons of Roman historical rulers (sorry, can’t help picking on the Romans) all committed heinous acts that destroyed real people’s lives. Their inhumanity can provide a very tactile, grim narrative element to your games, given further weight by the fact that they actually committed these crimes. They are real nightmares for your players to face, not made-up villains with fictitious crimes. Yet it’s for that reason we ought to make sure to play out their involvement in fictional stories with the most respect as possible. Because in the end, they murdered and terrorized and tormented real people, whose memory we’re messing with in our fictional worlds.

A good example of characters with terrifying historical backgrounds is one of America’s very first serial killers, Albert Fish. Hamilton Howard “Albert” Fish lived from 1870 to 1936 and during his time he committed some of the worst murders this country has ever seen, specifically targeting little boys for assault, murder, and eventual cannibalism. Reports speculate Fish killed anywhere from five to one hundred children in his lifetime before he was caught. When asked why he committed the unspeakable crimes, he is allegedly reported to have said…

It takes a special level of horrifying to imagine a man like Albert Fish for inclusion in your fictional stories, but history has provided you the blueprint for that horror in a real man, who committed real crimes against real children. Including a figure like Fish, or any number of other human criminals who perpetrated acts of depravity and slaughter, means recognizing these are people who harmed a real someone’s family member or child, not just a fictionalized person. And the historical weight of their crimes then becomes the backdrop for your game’s exploration.

To be respectful when including these historical figures, an important question to ask yourself is why. Why is it important to use this historical figure? What do they add to your story that a fictional character cannot? Are they integral to the plot or are they being utilized for the name recognition and shock value their crimes provide? If it’s the latter, then perhaps a long, hard look should be given towards why your game needs such a sensationalized pop provided by these figures. And if they are included, a strong eye should be put towards how these characters are being portrayed.

The universal example of this is Adolf Hitler. Hitler has appeared in so many media representations from Marvel Comics where he was punched out by Captain America (and recently by the maybe more awesome America Chavez) to his comedic performance in satirical shows like Look Who’s Back. While many use media representations of Hitler to jeer at and lampoon the genocidal dictator, the games world seems obsessed with including the Nazis and their leader as the ultimate bad guys, a two-dimensional representation of the ultimate evil. Yet most of those very games never address the real complex horrors of the atrocities committed, instead focusing their energy on the angry little man behind the awful mustache. Adolf Hitler’s very presence creates a titular evil to face without providing the human story of the suffering he created. He is the figurehead, an unexplained nightmare from our collective consciousness, a shorthand for Evil with a capital E.

For people like me, however, with a huge history of family members suffering in the Holocaust, the constant inclusion of Hitler and Nazis in games is a grating reminder of family tragedies not long passed. The same could be said for the inclusion of people like Osama Bin Laden, Joseph McCarthy, or Joseph Stalin in a game either as a figure. In a way, the historical figure question is almost a catch 22. When creating a game set in history, to exclude these figures would be to perpetrate the very white-washing I’m speaking against. But we shouldn’t be afraid to look at how much room and prominence these figures are being given, and how they are being represented.

But Shoshana, It’s Just A Game

While having these conversations, I inevitably run up against the same response from a section of people. “But Shoshana, it’s just a game. We’re just out to have a little fun. Don’t be such a party pooper. I like beating up Nazis without having a deep conversations about the Holocaust around the table. That sounds like the opposite of fun for my characters.” And yeah, I’d say it sure does. Players are coming to your table to enjoy themselves, not get into a deeply damaging exploration of the horrors of the Holocaust. They want to punch Nazis and feel satisfied by punching the worst evil humanity can imagine. Right? Sure.

But there are ways to acknowledge the evil done while still providing the experience you’re looking for in a fun game. A narrative can frame the context of events to take into account the difficulties, horrors, and complex social/cultural/religious issues by acknowledging their existence, and then place the game, its characters and its players on their path in contrast to and contextual relationship with these complicated events. One can still explore play the Inglorious Basterds going off to take Nazi scalps while acknowledging in the narrative the horrors that drove these Jewish soldiers to feel the need to fly all the way into Axis territory and commit some serious violence.

A Deeply Personal Favorite Example

It’s hard to consider the following example as a favorite of mine without acknowledging how difficult it is for me to even look at or read this book. When I heard White Wolf was putting out a book about the Holocaust as a sourcebook for their game Wraith: the Oblivion, I remember being outraged on a deep level in the first place. I thought there was no way anyone could have gotten a game book set during the Holocaust, not just World War II overall but the genocide of the Holocaust, correct in any meaningful way.

Then, I read Shoah: Charnel Houses of Europe.

Published under White Wolf’s Black Dog mature material label, Charnel Houses of Europe is a well-researched, thoughtful, respectful portrayal of the Holocaust in a game. I remember picking it up, ready to be angry, and instead read the book in shocked silence. I knew reading the book that the creators got it. They understood the enormity of the subject they were tackling and put back into their work their immense feelings in the shadow of such a horrifying tragedy. I remember coming across a single piece of art that cemented this feeling for me too.

In one picture, this book was sealed into my memory as the one of the best portrayal of the Holocaust in art that I’d ever seen. And as always, my hat’s off to the creative team.

This book highlights the importance of creating a good game as an element of being respectful. Many of the worst examples of disrespectful representation of difficult subject matter comes down to the fact that the material produce is just BAD. And by the inability of the artist or writer to do a good job tackling the enormity of a subject, their bad portrayal becomes disrespectful simply by clumsy handling. So when tackling rough issues in your work, it’s important to make sure you can jump the hurdle of being good too so your work has the chops to represent the material with the complexity needed.

Reflecting On Lost History

The last element of respectful representation lies in reflecting on the dominant narrative presented by both history and the Hollywood History provided by media, and delving deep into how that representation is either accurate or not. This is especially important when considering issues of marginalized populations or non-western cultures. For better or worse, western narratives have dominated the media landscape, and western bias has twisted the retelling of history in everything from academic research to our education systems. Yet we know from important research going on that history is far more complicated in terms of the lives of those outside the dominant narrative than previously provided to mainstream audiences.

Common statements that come up due to dominant narrative bias include:

- “But women didn’t have jobs in _______ era!”

- “But there were no people of color in _________!”

- “But there were no queer people out of the closet in _______!”

These are all byproducts of dominant narrative bias, as told thru the lens of history controlled by hetero-cis-white-male patriarchal views. Fact is, history is always way more interesting than we think and full of surprises for those who think women didn’t have freedom before the suffragette movement, or who believe there were no Jews or prominent people of color in Europe before the twentieth century.

With just a little Google-fu you can come up with examples of prominent people of color all across Europe and the United States, moving through white society in defiance of expectation. We see queer relationships reflected in historical figures, such as Alexander the Great, who conquered what many saw as the ‘known world’ at the time (another super western-centric idea back during Greek times) with his spouse and multiple lovers of multiple genders at his side. And I won’t even get started on where Jews have lived and what they’ve done, because to paraphrase the song, we’ve been everywhere, man, from China to Africa, across Middle Eastern countries to the wild west. And thanks to amazing people doing fantastic research these days, we don’t have to just rely on the dominant narrative or biased educational institutions to teach us how things really were. We have the internet to give us more information.

(Of course one ought to check their sources to make sure they’re reliable. There are way too many ‘alternative facts’ out there to just accept things without verification. Always check to make sure your sources are reliable or risk spreading the virus of rewritten history).

In short, do not just swallow the dominant narrative and regurgitate it into your games. History is way more interesting than you might think. And by doing a little research, you can provide a more realistic portrayal of not only dominant groups, but marginalized groups as well, such as women, queer people, people of color, disabled people, and people of different genders, ethnicities, religious and cultural groups.

Why Is All This Important?

So after all this exploring of respectful history representation we come down to the last and maybe most important question: why is this important? Why is it important to represent history well in your games? There’s a few simple answers.

- By providing a respectful historical context for your game, you acknowledge the enormity of historical tragedies and events gone by.

- You acknowledge and respect the fact that those historical events might have a serious impact on people playing your game based on their own background or else just sensitivity to the subject matter.

- You explore more complicated historical narratives and help bring forth those lost narratives into the media eye by representing them in your stories.

- You provide richer narrative portrayals of characters for your players to inhabit, giving room for different stories especially for marginalized people in the game space.

But if you want to put aside all of this, here’s the one major reason to keep in mind:

You’ll just tell better stories.

If you spend all your time retreading the same historical ground done by the two-dimensional historic representations of the dominant narrative, your game will be limited to only those standard representations. By expanding the field of your representation of history, and by exploring the complexity of history in a more contextualized and nuanced light, you’ll be able to tell new and richer stories with your games and set yourself on a path to making better art in the long run.

So in closing, go make better art thanks to proper historical context. It might open up worlds of stories you never expected.