I got an email this afternoon. It, like many other emails recently, disappeared into my overzealous spam filter (which rules my inbox like a terrifying digital helicopter parent) so I only discovered it late after midnight. It was a message from Ancestry.com. At first, I thought it was spam and therefore had been sent appropriately into the oubliette to be forever ignored. But then the subject caught my eye. “LOOKING FOR MY DAD.”

I stopped. It wasn’t an ad. It was an actual message from someone who was looking for her father. I didn’t hesitate. I clicked on the link. In the message, a young woman asked me if I knew about my biological family. She said Ancestry.com had matched our DNA and said we were cousins. She’d been looking for her father, could I help her out.

It was only then I remembered I’d done one of those swab-your-mouth DNA tests and sent it off months ago. I’d forgotten all about it. I politely penned back a message apologizing for my inability to help the young woman. I explained I was adopted and didn’t have any information about my biological family. I clicked send, then looked up at the menu bar across the top that said DNA.

This is it, I figured. The moment of truth. I’d get a chance to prove what the adoption papers said was true, justify every time someone asked me about my ancestry and I proudly recited what those dang papers told me. See, I’d been told by some very vague pieces of paper that my genetic family was Irish and Scottish and Scandinavian and Native America. Specifically, that they were at least 1/4 Cherokee. And there was going to be my DNA results, right there for me to see.

So I clicked the button.

And apparently discovered I was complicit in some serious multi-generational cultural appropriation.

When I was eleven years old, my parents told me I was adopted. There’s a weird story involved, in which I was reading a Babysitter’s Club Book in which Claudia believes she’s adopted and goes on this wild goose chase to discover why she’s so different than her family. And I laughed about it in my eleven-year-old way to my parents, who then sat me down and told me I actually WAS adopted, unlike Claudia, who only learns a valuable lesson about being different in her own special way. I instead learned that sometimes, the universe has a perverse sense of humor.

My parents didn’t have a hell of a lot of documents about the adoption. I’d been given up as an infant by my birth family, signed away in a closed adoption before I was even born to a private agency who specialized in matching couples by their ‘appearance compatibility.’ By the time years later I wanted to look into my biological family, that agency had long since closed and their records disappeared into the darkness of the pre-digital age. ‘Uncle Ray’ and ‘Auntie Barbara’ were the adoption brokers, the heads of the agency, and not just family friends as I’d imagined when I was growing up.

I remember being my eleven-year-old self, sitting on my parents’ bed while my mother pulled out a manila envelope. In there were some documents, like the adoption certificate, and some papers she kept, photocopies of records about the birth family. The adoption was sealed but there were some basic intake records of the family, descriptions of their background, heritage, what the family members were like, without names or indications of where they were from. They listed in those documents their heritage as Irish / Scottish / Scandinavian / Native American. In fact, the descriptions of the family members had been very specific that they were Cherokee, that they were about one quarter Cherokee in fact, and they were closely tied to that heritage. That was right there, in the descriptors.

As a little girl, I’d clung to that information. There I was, eleven, having just found out I was genetically not related to my adopted parents. The family and community I had was mine by adoption. And while that means they were indeed my family, I developed that yearning a lot of adopted kids talk about to connect with something from their biological past. I looked at that paper before my mother whisked it away, hid it from me, as she did many things about that adoption. But later, when kids would tease me in school for being adopted (and they did, telling me the reason my parents wouldn’t send me on trips we couldn’t legitimately afford was because I wasn’t their real child), I’d proudly recite what I knew about my lineage. It became my only connection to my past. In a school full of Eastern European descended Jews, I was the Irish/Scottish/Scandinavian/Cherokee girl. I was different.

By the time I was in college, however, the information on that little piece of paper wasn’t a way to be different. It was a lifeline to somewhere out in the rest of the world, beyond the walls of my orthodox upbringing, to a place where there might be other people who were my genetic relatives. Maybe, somewhere out there, there was someone who knew where I came from. And that road led to a community of people indigenous to this continent, not far away in Europe. A group of people who, if you tied together the pieces of information in that long-ago read document, were from Kentucky and lived close to a Cherokee reservation in recent generations. I held onto that information ferociously, as my only link to the somewhere I’d come from and might eventually find again.

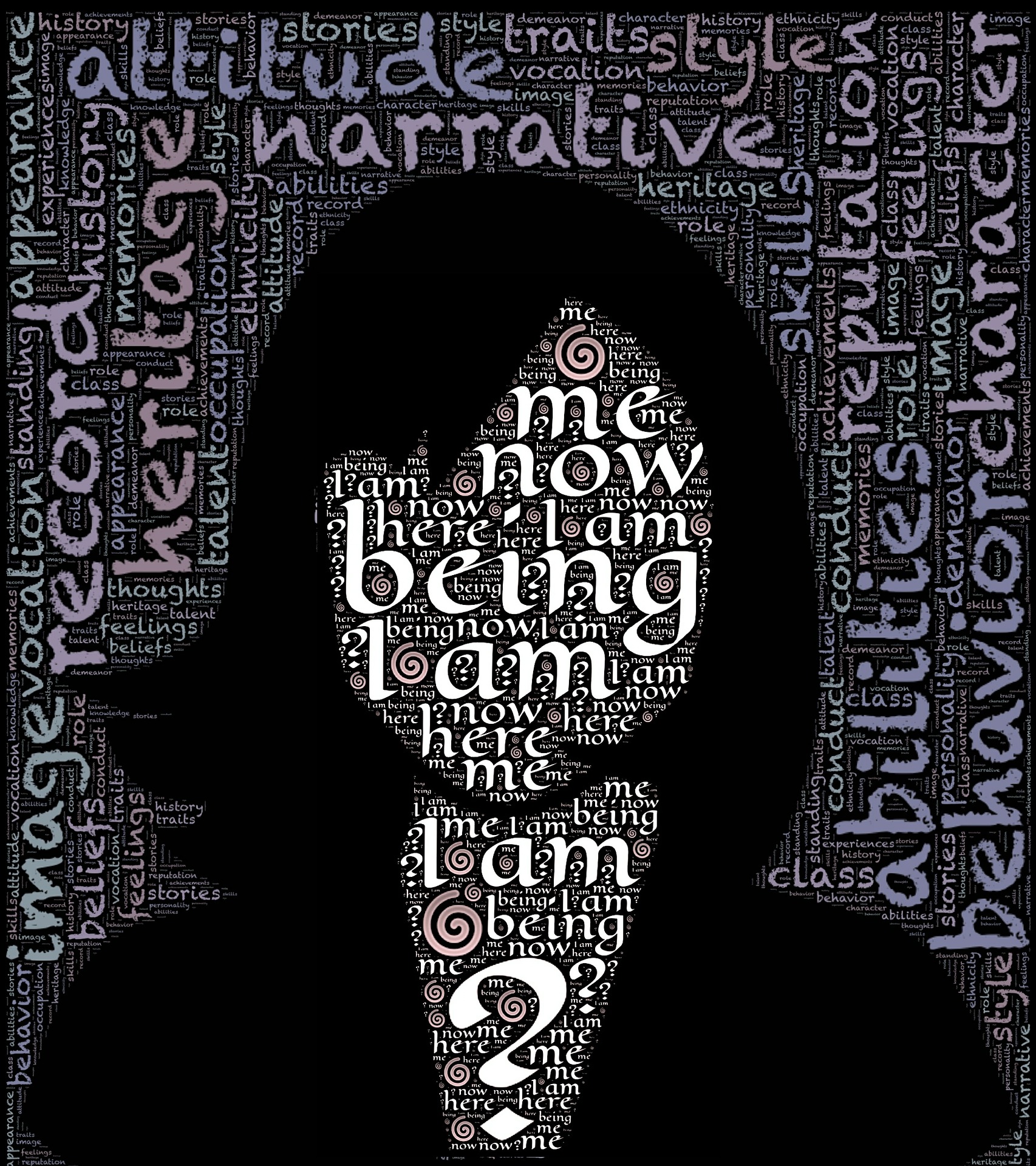

Everyone wants to know where they belong. And I know for me, a huge part of feeling unmoored in this great wide world has been because of a lack of knowledge of my biological heritage. To many people, ancestry isn’t important. They are happy to live in the now. But I believe connections to the past help us point proudly to where we’ve come from and say “Come better or worse, this is where I began, and this is where I walk now.” And you root yourself in the stories of that culture where you can, make it a part of your story, your identity.

When people asked what it was like to have Native American ancestry, I’d say, “I don’t know, I don’t live that cultural life, but I’m 1/4 by blood” because that’s what the paper told me.

And the paper. Fucking. Lied.

People criticize these new DNA tests that have become all the rage. It’s been discovered some of the companies might be selling our DNA information. After tonight, I figure I’ve got other things to worry about rather than being concerned someone is going to map my lost little genome.

You see, it turns out, whoever filled out those papers my mother showed me when I was eleven was either tragically misinformed or had a very estranged relationship with the truth. Otherwise, there was one HELL of a mix up with the copy machine that day.

If Ancestry.com is correct, I’m actually not even a little Native American. Not one lick. I’m indeed Irish/Scottish/Welsh by a good mount. I’m also super British (like 54%). There’s some mixed up western Europe in there too. And yes, I am Scandinavian – I’m Finnish! But there isn’t a single lick of Cherokee in there. In fact, somewhere in my ancestry someone apparently dipped their toes into the gene pool in India. I’m more INDIAN than Native American. But nope, not a little Cherokee. Not a bit. Zip.

It took a few minutes for this to settle in on me. I’ve been having a weird week, or at least I’d thought it was weird BEFORE this happened. As I’ve said, the universe just has a perverse sense of humor. Because just when you think you know at least some basic things about yourself, the universe yanks the carpet out from under you once again. And here I’d sent an email to this nice young woman saying I didn’t know anything about my ancestry. But I’d at least believed I had a few pieces of information settled. Turns out that wasn’t the case after all.

Then I thought about the last few months, and some work I’d done in my professional career, and a whole other consideration came crashing down on my shoulders.

See, I’d spent time talking in my career about representation in games and fiction. I’d talked about the importance of avoiding cultural appropriation and identity appropriation. And while I had NEVER represented myself as someone who lived the life of an indigenous person, I had in the past talked about feeling connected to my heritage and the importance of recognizing the confusion over being someone who had ancestry that was from indigenous people of the United States while being disconnected from that heritage and overall also white. I stated again and again that though I had no connection to my biological family, I had grown up (from that age of eleven) acutely aware of the weird place of being someone white as hell who had native ancestry, even a little. I winced at every person who made claims about how much they were an “Indian Princess” and never tried to be THAT girl. Instead, I tried to cultivate a sensitivity to the idea of appropriation, of issues facing indigenous people, all the while balancing it out with the one drilled in thought: the paper might say you’re 1/4 Cherokee, but you are a white girl. That is your privilege. Don’t forget that.

And yet.

And yet.

Some part of me said, “this is also a part of you.” Some part of me said “those documents tell you who your family is genetically, who they are by blood, who YOU ARE by blood. And that has to mean something. Do you have the right to say you’re happy about your connection to a background? Not happy or proud in the shitty superiority way, but in the speak with joy and happiness about coming from somewhere kind of pride, somewhere vibrant and real?”

And I was happy, even proud (though isn’t that a loaded word these days?) I was happy that little document had given me something to say about where I came from. It made me develop a personal relationship with the historical narratives I came in contact with of native people, of rich cultures and diverse voices and also of ongoing genocide and destruction in the United States that felt a little bit more personal for the connection I felt to my genetics.

Now as I look back at those feelings, I want to laugh at myself and hide. Because of course that narrative of the genocide of native people was always important, and I’d never take away from it. But it was never my narrative. A little paper lied to me. Whoever told that story had appropriated a culture for their own needs, whatever those were at the time. And thanks to that little paper, I’ve been appropriating native identity since I was eleven and didn’t even know it.

The idea makes me sick to my stomach. And ashamed. And more conflicted then ever about what the hell being adopted and unmoored from my genetic ancestry means. It makes me question whether genetic ancestry means anything at all, whether a person in my position is just stuck in the middle, neither the bearer of a long legacy by blood or the bearer of a legacy of another legacy not entirely ever your own. I thought these feelings were complicated BEFORE. Now I’m not sure what the hell to do with them at all.

So I’m dealing with it the only way I know how: by feeling guilty, by being overly intellectual and analytical, and by writing about it.

I’m recontextualizing my feelings on a whole part of my identity I thought I’d known for certain. It’s not as though I have to go out and rescind some grand letters, resign from organizations, hand in some cred card. When it comes to personal relationships with identity, that’s not how shit works. (Or it might if you found this out and were legitimately part of some heritage organization. Thank God that’s not the situation here). But in the meanwhile, this whole thing has brought to the forefront two feelings:

One: someone in my background needs to get kicked seriously in the face for lying on a very important piece of paper.

Two: Feeling connected to your identity is a complex relationship when you’re adopted, and it can lead to trying to find anything, anywhere, to give you a sense of belonging. And in this case, it led me to a lie which I then apparently perpetuated without even knowing. A lie which only further tangles up my feelings on identity as a whole.

I’m not entirely sure how I’ll unfuck that particular Gordian knot. I’m writing this blog post, first of all. And I may have made a number of jokes in the last little while about now being absolutely CERTAIN I’m the whitest white girl I know. Most of them were told in my typical sardonic sense of humor sort of way. But this time they’re laced with a layer of serious self-depreciation sprinkled with a whole lot of embarrassment and shame. Because like it or not, I did appropriate another culture. And maybe that says more about where we ought to hang our hats in regards to appropriation and identity politics in the first place.

There have been long talks about what makes someone ‘count’ when speaking about their particular heritage. I’ve had friends talk to me about not feeling ‘enough’ of something to count as a member of their own genetic background. And I previously thought I’d had a dog in that fight, conflicted about whether or not having a quarter Cherokee blood meant I had a right to feel any connection at ALL to a group of people whose plight I’d never experienced due to being, well, who I am in appearance and life experience. I grew up a New York very white Jewish girl who, I thought, was also a quarter Native American. And I’d had a complicated relationship with that.

And now it’s even MORE complicated knowing I’ve been effectively perpetuating a lie.

There’s going to be more sardonic self-deprecating humor, and embarrassment, for at least a little while. But one thing I’m taking away from this whole debacle is this:

I’d spent my time since I was eleven years old supremely conscious of the plight of indigenous people, not only because it was an important issue and cause on its own, but because I’d felt a personal connection. I’d engaged in conversations about identity politics and complicated relationships with race, culture, and representation overall because in one moment when I was eleven, a single piece of paper set me on that path. I tried (often in my own inept way) to be well-informed, well-spoken, respectful, and helpful, as much as a woman in my privileged position could be without falling into the hole of being a white feminist of the worst sort. A lot of the origins of my interest in these things, even when I was growing up in a very sheltered and very xenophobic community, was based on this knowledge given to me by a tiny piece of paper, telling me I was someone with a background rooted in the history of a marginalized people.

And even if that paper lied to me in the worst way, the years of trying to be conscious of these issues can’t be erased by a single genetic test. I won’t ever, EVER, claim again a familial connection to indigenous people – of course I wouldn’t. But my concern over issues of representation, of equality, of justice for native people? That’s not going to change. And my stumbling, earnest attempts at being a good ally continue as they are, mired in their privilege even more now than before. If anything, this revelation just makes me more aware of the complexity of cultural identity and appropriation, and how conversations need to continue happening about what identity truly means to us in our modern world.

Meanwhile, I’m going to look through my mother’s things, put aside in a box after her death, to try to find this damn piece of paper again. It seems to have disappeared along with many of my mother’s other important papers (she wasn’t very organized). But I am going to try and find it so that perhaps one day soon I can have the joy of crumpling it up, kicking it across the room, yelling at it, and then maybe burning it. Because sometimes you just gotta get out those complicated feelings the old-fashioned way: through an expression of well-justified fury.

Or I might just hang onto it as a reminder of how real and serious appropriation is and the damage it can do in so many different directions. And of the universe’s ongoing and perpetual sense of perverse humor.