First, I’m going to start off by saying this essay is a direct response to a conversation going on in the larp community right now, started by a few other essays including one by Ericka Skirpan regarding Playing To Win at larp. This article stirred up some controversy recently because of the stated thesis that should a player approach larps with the aim of ‘winning’ as a solitary goal, then perhaps larping isn’t for that player. The article states:

“If you are in LARP to play solo-Nerdball [a term originating in an article by Matthew Webb regarding inherently selfish, individualistic style play], LARP is not the right hobby for you. If a player’s pure and only enjoyment in a game comes out of the fact that they need the most points, stats, or mechanical advantages over other players, then LARP is not the gaming medium that person should be devoting their energy to playing.”

This in itself, in my opinion, is not as controversial a declaration as some might think. The notion of viewing one’s own empowerment and achievement in a shared environment as more important than the fun and achievement of others is a problematic one at best because it recognizes the selfish goal of self-fulfillment over the needs and wants of others. However, is there a way to strive for your own goals in a game while still recognizing the needs of others and even go so far as to help the other achieve their goal? All the while still allowing for the drama and potential excitement of antagonistic play?

The fundamental answer, I believe, lies in a single question, one often thrown around by actors everywhere: what’s my motivation?

Who Doesn’t Want To Win?

Before we get into the solutions, let’s take a look at how we got here a little bit. I’m going to throw on my Game Studies brain for a second, and thank the NYU Game Center Masters program for making me learn all this game history. Strap in, folks, here we go.

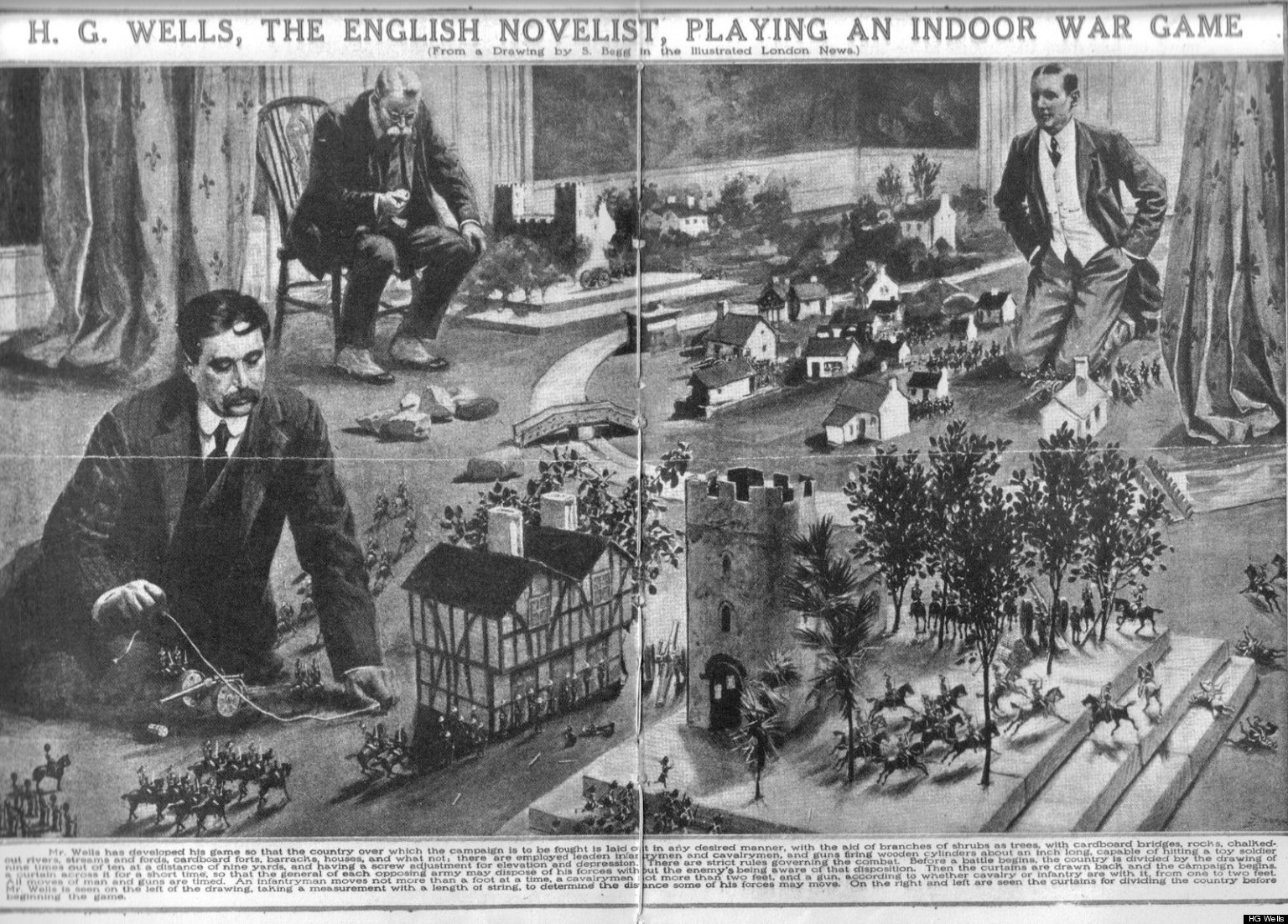

The notion of Play To Win, with its origins in competitive gaming culture, has its roots in the early simulationist styles of play which historically predicated much of what we’d call modern gaming. Many early games, from chess to old Kriegsspiel (or war games), were conflict or competition simulations, intended to replicate states of power struggles between armies or oppositional groups. They replicated standard power structures we expect out of our world: people or groups strive against one another, winners beat losers, the game ends.

Tabletop roleplaying games and video games copied these same models for much of games history, providing goals for the players which involve striving against a competing power structure to achieve their goals. They need to overcome obstacles, slay the foe, even outthink an opponent. Some games even perpetuate a culture of considering the game system itself (be it the video game and its designers, or the tabletop GM) to be a force they strive against for victory. This gave rise, in my opinion, to the notion of the game master or game designer as the enemy, the obstacle to be outmaneuvered and conquered to achieve victory.

This perpetual state of striving against an oppressive force, battling for power against an oppositional system, is baked into even the most story-driven game. By nature, dramatic action is created by striving against something to attain a goal. Even in the more recent evolution of games which accommodate more narrativist thinking copy these power dynamics in many (if not all?) their narrative choices. It’s the tale as old as time. Beowolf strives against a monster and its Mommy Dearest. David against Goliath. Oppositional forces create tension. Without Sauron to fight against, Lord of the Rings would just be about a brisk jaunt to see a very pretty volcano. Without Panem’s oppressive government, Katniss’s story in The Hunger Games would be about a girl getting her chance to be on television. And while those stories can be fun (pastoral narratives can be very pretty), dramatic storytelling – and therefore in games oppositional design creating dramatic and exciting play – are driven by competition.

If that is the case, then I believe expecting competitive attitudes to be absent or diminished in live action games is, inherently, expecting people to embrace a massive shift in their expectations about dramatic structure. We as players and consumers of narrative content have been hardwired to expect our characters to have to strive against power structures and opposition. How then do we expect characters and larpers to not identify other characters and their players as oppositional forces to be overcome?

How can we deny that these ideas have been baked into our game culture so long so as to become second nature? And how can we expect players to ignore actions taken by others in opposition to their goals, when even the narratives we create in cooperative story environments are predicated on the idea of striving against forces in competition for our own prefered win state?

In short: we have been telling stories about competing since the dawn of time. Then we’re putting our players in situations where they must strive in their narratives against forces put in place by the game designers. If they’re recognizing the game as having competitive forces anyway, why wouldn’t they see their fellow players as antagonists? Plenty of other things in the dramatic structure are their opposition already!

With this giant structural framework already in place encouraging competition for resources in our players and their characters, the question becomes: how do we aim to de-incentivize Playing To Win for individual goals so we can have the cooperative space for play we want?

And my answer is: you don’t. You don’t deconstruct the instinct to Play to Win. Instead, you harness it by refocusing just what Winning means, looking past viewing goal based achievement as a win state, and instead creating shared win conditions based on recognized motivations in opposing characters.

Simply put: we look not at the goal, but the WHY behind the goal. Because in recognizing WHY characters compete and identifying just what they’re competing for, we can not only construct a framework for combating toxic Play to Win play strategy, we can encourage cooperative play and reframe the dialogue about what winning truly means.

“Part fools! / Put up your swords. You know not what you do.”

This quote from Romeo and Juliet, delivered so well in my opinion in the 90’s Baz Luhrmann retelling, is the quote that comes to mind when I think of the motivations behind play styles in larps. When players enter a play space, embodying their characters for a play session, often times there isn’t a lot of time for examining a character’s motivations. The immediacy of larps, much like the immediacy of events in real life, requires players to react much faster than, say, a player might when playing a tabletop roleplaying game. There, players may break character to discuss their options more freely (although many playgroups cut down on that sort of behavior to simulate that said immediacy). It is far easier to examine the motivations behind a character’s actions when you have the chance to break character and really have a good think.

In larp, the actions one takes are often quick, driven by the mindset a player has taken on for the duration of character play. This embodiment of the character simulates in many ways the immediacy needed to engage in improv acting. One must react spontaneously, driven only by the way a player understands their character. When reacting, a player in a larp may engage in actions that are driven by the fundamental needs their character has as they understand them in the moment. And when presented with obstacles to overcome, challenges to their goals or their authority, or simple antagonism, a player may respond as their character would – with the knee-jerk one would expect in a real-life antagonistic situation – rather than sitting back to examine the full motivations behind why the scene has become antagonistic.

It is this why I believe lies at the heart of how we can tackle the issue of truly antagonistic situations in larp, and address why Play To Win can be a toxic mindset – and how it doesn’t have to be.

When engaging in a struggle between two characters over a goal, a player is recognizing only their own goals as valid in the situation, and view the other character involved in that struggle as an oppositional force rather than a cooperative element in their play. They push aside the needs of the other, often times not taking the time to consider why the other character has become said obstacle. Yet should lines of communication be opened between players during play, both players may find by understanding each other’s motivations rather than relying on a knee-jerk reaction, they can find ways to achieve both goals in a satisfactory manner.

This adjustment to a player’s mindset does not mean the players require long negotiations to make sure the antagonistic situation just ends and has a happy ending for everyone involved. Antagonistic action has a place in narrative, as we’ve pointed out above. However, instead of recognizing only their character’s motivations and actions as valid, understanding the other character’s needs and motivations can allow the players involved to course correct in their own playstyle. This correction makes room for both to reach a fulfilling end to their antagonism rather than focusing on only one successful outcome: an outcome which leaves one the winner and one the loser.

An Example: Susan and Edward’s Characters And The Fiefdom Fight

I’ll provide an example:

- Susan and Edward are playing two characters who are fighting over the same fiefdom in a medieval fantasy game. Susan’s character is driven by the motivation that she must take the fiefdom so she can bring its armies to bear against her brother’s kidnapper. Her character is driven by the need to save her brother, not by the need for power and glory. Meanwhile, Edward’s character’s goal is to gain the fiefdom to attain personal power, because he is driven by the need to control the chaos of the world around him and provide what he perceives as order. He is driven by his own view of the world and what he believes is serving the greater good.

- Susan and Edward’s characters are striving against one another for this fiefdom. Without understanding the reasons behind the others’ character motivations, their reactions in game would be uninformed by what the other player needs to get out of the circumstance to achieve a satisfactory result in their play. As Susan makes moves to get the fiefdom for her character before Edward’s character can, Edward can become increasingly frustrated because his play is not reaching a fulfilling goal, his character’s motivations (and therefore a core tenant of his character’s mindset) going unfulfilled.

- To avoid that unfulfillment creating tension between Susan and Edward, when the two recognize their characters have entered an antagonistic situation, they share a conversation regarding just what their characters want in the game. Not simply what their goals are, because that has become obvious. But what MOTIVATES those character’s actions. They begin to understand the psychology behind the other character’s actions, outside of the player’s own need to fulfill those character’s goals.

- Susan and Edward then reenter play, now understanding the needs of the other. They can then shape their play accordingly, understanding also that the other player is not there to ruin their time, but is informed about what the other would want as part of their resolution. Susan’s character isn’t interested in the fiefdom, for example – she just wants her brother back. Edward can then steer his character towards recognizing Susan’s character’s need and find a way to achieve a solution that works for both of them. They continue their competition, but if Edward wins, he pledges to help Susan’s character get her brother back. While if Susan wins, she brings on Edward’s character to help achieve order in the fiefdom, satisfying his need as well.

So What’s The Catch?

Now, this strategy for cooperative play requires several accepted rules, better explicitly shared rather than implicitly expected, going into the game. These social contracts must be laid out as part of the play culture of the game for this motivation-based Play To Win style to work.

- Players must accept that antagonism is only in character and not motivated by player antagonism (CvC versus PvP).

- Players must assume positive intent when entering into this style of play. This is a fundamental social contract which I believe should be expected as part of larping in general to create a cooperative narrative environment, but it is explicitly required when sharing motivational-driven play.

- Players must consider each other’s character goals as just as valid as their own, to be respected as co-evolving story threads rather than simple oppositions to be destroyed in the pursuit of their own character’s success.

- Players must embrace a level of trust, that the other player – once they understand the other character’s motivations – will consider a blended ending to the competition which allows even the ‘loser’ to achieve a satisfactory stepping stone to their own story’s goal achievement. The losing character may not win their initial goal, but the winning character’s player will help steer the outcome towards a next-step for their co-player to achieve their aims.

- Players must maintain out of character communication (as laid out in Craig Page’s response essay entitled “How Playing To Win Can Work”) to make sure the players can check in with one another should the level of antagonism begin to bleed into the out of character realm.

Sounds complicated, with a lot of caveats? I never said this style of gaming cooperation would be entirely easy. Yet this kind of paradigm shift, I believe, can open up a whole new way of looking at what Winning really means in our games. Winning becomes a state of motivational recognition and fulfillment rather than goal-oriented success. For the ‘losers’ in a competition in character can then know they may have lost initially, but their striving to win will have satisfactory opportunities just around the corner, facilitated by their co-players.

So after all that, here’s my suggestion: let’s try to look at one another’s characters not as obstacles, or another player as an opposing force, but simply as a force with separate motivations to be respected as you play to fulfill your own character’s motivations. Together, by respecting what drives both characters (and therefore what drives a player’s actions in-game) we can better understand how to make us all win in the end, together.